|

JUXTAPOZ Issue #42, January 2003 Alex Grey Visionary voyeur ALEX GREY proves reality is only skin-deep.

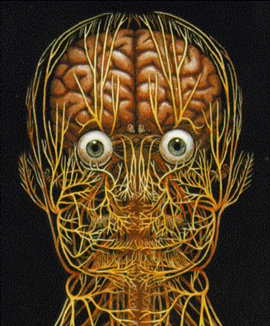

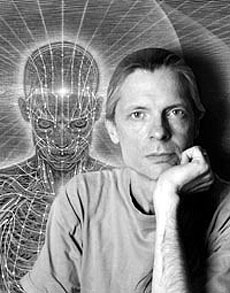

Alex Grey: painter, illustrator, author, teacher, psychedelic proselytizer, groovin‘ guru, father of future film starlet Zena Grey, husband of visionary ambient painter Allyson Grey, et cetera. His mind’s a portal to bliss, his paint-brush a flower of light — he dissects consciousness like a tripping coroner, peeling back mortal coils to reveal fantastic spiritual beings trapped inside spatial bodies. Plenty of psycho-currents find confluence in his unique universe. Television viewers caught his punditry, presented on Discovery Channel’s acclaimed mind/creativity feature The Brain: Our Universe Within. Students and curious ones caught his art history/mystery classes at NYU, the Omega Institute, and Naropa. New Age consumers purchase his recorded lecture series The Visionary Artist. He even invented Mindfold, a light-blocking relaxation aid sold around the world. But his incredible oil paintings set him apart from run-of-the-mill Renaissance Men. In two dimensions he magically depicts our collective spiritual experience, alternating tradition and invention in heretofore unexplored painterly ways. “The mission of art is to make the soul perceptible,” he says. Obviously! Medical researchers know him for his dynamic body-energy diagrams. Mystics know him for his beautiful graphics adorning everything from Tool and Beastie Boys CDs to his own tome The Mission Of Art. Of course Juxtapoz readers respond positively to his far-out representations of their own out-of-body experiences. His paintings present blissed-out meditators and eternally-embracing lovers, exhibiting what he describes as “qualities common to all mystical experiences — a sense of unity, a unity within one’s self and a unity with the All; transcendence of time and space — “My artwork also reflects the notion that we’re related to the stars. If the Earth and the Sun are basically cosmic dust, then what else could we be made of? If the same shit that built the stars is running through us, then there’s a web of infinite interconnectedness. I try to point to that with my artwork through a new kind of iconography not dependent on pre-existing sacred traditions, but evocative of the truths inherent in those traditions. “The perennial philosophy at the core of truth as understood by the various sacred traditions informs my work. Sacred art has to point to teachings.” Alex, is your art sacred? “Yes, it aspires to that. It points to a way of knowing about ourselves and our possibilities for self-liberation.”

Alex, a quintessential Sagittarius, joined the human race 11/29/53. “My dad was what they once called a ‘commercial artist’ — a graphic designer — he’s the one who taught me how to draw. His name was Walt Velzy. ‘Grey’ was a name that I decided on. I had one of those life-changing experiences the first time I took acid — I’d been doing performance art about polarities. I’d gone to the north magnetic pole, I’d shaved half my hair off — to me it was all about embodying opposites. So, on my first acid trip, I was in a tunnel, and I was in the dark, going toward the light, and gray was the connection point between the opposites. And so it became a metaphor for me, to bridge the polarities and bring opposites together. I changed my name legally.” (Surfers will recognize the name Velzy as in Velzy Surfboards, finely fashioned tube-hangers ridden wherever waves are crashing.) The work of Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary loomed largely in the artist’s world view. Science and art, mind and body, all combined into a holistic appreciation of nature. Grey: “I’m awestruck by the way science has extended our vision. Using electron microscopy, using the Hubble telescope, expanding our visual understanding of the universe — as artists we have access to that information, while artists of the past had no idea about it. Dig this — in the Twentieth Century we first learned about Paleolithic art! Prior to the Nineteenth Century, nobody knew there was painting 20,000 years ago.” Optimism didn’t epitomize the artist’s early output. Rather, a morbid anxiety prevailed. His gig throughout the 70s as an autopsy-and-embalming assistant afforded grim perspectives of life’s fragility. Confrontational best describes his art from those days. Nude, one side of his head shaved, the other sprouting shoulder-length hair, he adorned billboards with his own likeness. Dressed as a soldier, he stamped ‘666’ onto the foreheads of passers-by. He and wife Allyson performed with cadavers and the Grim Reaper. Despite the heaviness of his subjects, he managed to wrest hope from the world’s psychological wreckage. “There’s truth to nihilism that I understand very clearly,” he says. This writer asks, Isn’t nihilism the great gravitational force that pulls the soul back into nothingness? Mustn’t we transcend it? “Yes,” the artist responds, “it’s also a way of realistically looking at how we treat each other. There’s so many instances of humans causing suffering rather than alleviating it…” Have we been around a long time, or are we so new a species that we haven’t worked it all out yet? Grey: “I think we’re in our adolescence as a species, and this is a dangerous time for humanity — just like my own adolescence, which was a troubled time — big suicide time, big addiction time, big struggles with relationships. Humanity’s having this meltdown, as we determine whether we can mature as a species, recognize our connection with the web of life, treat the Earth in a more friendly way, and invest in a sustainable future — these are issues of adulthood.” Can we make it? The artist, guarded, pauses. “Basically we have a fifty-fifty chance. It’s tenuous. It’s hopeful. You can say it’s propaganda, but I’d rather posit the possibility of healing, survival, and transformation, rather than only feel like the victim of the forces around us that seem nefarious and by which we feel imprisoned.” The artist comments on his legacy as a medical illustrator: “I started the Sacred Mirrors paintings back in 1979, and some doctors saw them, and they said, ‘Hey, you could do medical illustration, and we can get you a job.’ So, I got into medical illustration through my painting. I was preparing bodies in a medical school, at not-very-good wages, and a medical illustrator made considerably more — so that’s what I did for about twelve years — I illustrated medical books, brochures, and medical advertising. My first medical illustration was a brain and my last was a beautifully rendered rectum. I knew that was the end.” Your resumé please. “I went to Columbus College of Art and Design in Columbus, Ohio. I had a four-year scholarship but I quit — I couldn’t stand it.”

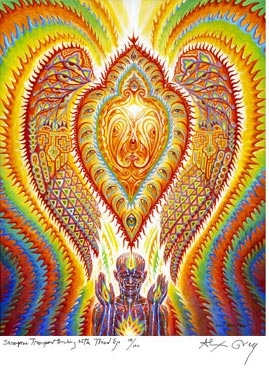

Darkness enshrouding the artist’s early output eventually lightened up. One cannot appreciate the sublime beauty of nature, and our own splendid place within it, without acknowledging an imperative for peace and tranquility. Grey’s work matured into an easy-to-view yet intense record of an inner quest. Does it attempt to literally represent metaphysical visions? “Sure,” he says. Is it, forgive the term, “visionary”??? Grey: “You know, that’s a maligned and overused term, but the art definitely corresponds to the visions I’ve had, some of which I’ve tried to translate directly from psychedelic voyages. One of my most popular paintings, Theologue, was from an LSD experience. I was seated in the lotus position, blindfolded, and when I looked out into space there was an electric perspective grid all along the horizon. It’s as if I was seeing the grid that the imagination uses to create the illusion of space. When you dream, the mind creates a compelling spatial environment. I was watching the naked grid underlying that space-making faculty of the mind. Painting is a projection of the mind, just as our interpretation of reality is a projection of the mind. Art is basically a portal into the artist’s imagination. “The imagination is a marvelous power, and as artists we’re purveyors of the hope creativity gives.” His work extrapolates spirituality’s visual vocabulary, established over the centuries. “Holy people glow — coronas and auras, fields of energy — we’re conditioned to the effect by looking at sacred art from all different world cultures. Visionary luminosity is a theme, a sacred stylistic trend. That’s why they call it ‘enlightenment.’” Marching onward, he bucks the trends. “In the Twentieth Century, art went through a purging of sacred imagery. Religion ran aground from dogma. And, sacred art traditions are not built on innovation but rather on repetition. In the West we thrive on novelty, and the notion of the individual making their own mark. Art went on an ego trip. Painters became almost religious figures.” Alex’s lovely wife Allyson paints ambient psychedelic/cyberdelic op-art with a spectral twist. Evocative of — yet predating — the pixilated dotscapes of blown-up computer art, her work reflects realms of automated alchemical joy. Hey, this isn’t a plug for the guy’s old lady, included herein as a shout-out to protocol. It’s no secret that Alex’s fame overshadows her own; many factors govern relationships between hard-chargin‘ artists, and often such discrepancies arise. This writer is, however, here to tell you that Allyson in fact kicks ass as a painter, and accordingly informs her husband’s work. Her relevance to this account goes without saying. Let’s skip pedestrian facts — such as, the couple married in 1975 — and examine Allyson’s role in the Grey universe. Her paintings hang throughout the familial Brooklyn loft, abstract counterpoint to her husband’s more realistic endeavors. Her colors unfold into eternity; Alex, on the other hand, paints primarily in the reds-and-blues of medical illustration. When seen together, the paintings compliment each other, completing a chromatic wonderland. Too bad Allyson’s stuff doesn’t get out there more. Whatever the reason might be, no one could doubt that she’ll eventually rank highly in the art hierarchy. Her physical and spiritual intercourse with Alex serves as subject matter for several of his paintings, some of which read as erotic, or even downright pornographic. Do the sexy, well-hung, well-endowed figures mean his stuff’s in any way risqué? Alex: “I try to put love into it — I don’t know how hot it is, in terms of whether it would be a turn-on to people — I think that seeing all the bones and guts and things like that for some people is a bit of a turn-off and for some, a turn-on. For me it’s sexy. It’s like inter-dimensional sex. Sex when you’re tripping is some of the most incredible sex you can have. My work points to a non-conventional sexual experience — ultimately I’d like it to point to a trans-gender union experience.” The couple’s gorgeous daughter Zena appears in many Hollywood films, like The Bone Collector, Snow Day, and Summer Catch. She’s a pro; the parents definitely let her do her own thing. Alex: “We decided to support her in her self-actualization as an actress, and see what happened. Call it indulgence or whatever — she’s a great kid. She’s thirteen now; she’s a Scorpio, and a very passionate and committed person.” She’s gonna be a hot commodity among future moguls, that’s for sure!

Nobody paints quite like Alex Grey. Both ancient and modern, his work reflects a society in transition, altered states of consciousness, and ultimately death. Is it Pop? Is it Underground? New Age? Psychedelic? Sacred? Who knows. Exactly how does he bring a painting to life? “The vision comes first for me — for a lot of painters it’s different, they start working and something emerges. For me it always starts with something from some experience. A vision first, and then I start to interpret it — it arrives sort of like a cosmic FedEx. The vision might be a very brief glimpse, or it might be an extended mindfuck. And then, I make a sketch from that. Those drawings are typically crude, then further sketches become refined if I think the idea has merit, or the image has recurred numerous times. Sometimes the same vision occurs over and over again, and I say, ‘I guess I gotta do that one.’ From there I execute a fairly complete drawing that often takes a long time.” Then comes a watercolor rendering. What appears to this writer as a exquisitely completed piece is merely the study for something much larger, which is in turn a study for something larger still, ad infinitum. “Some of my paintings, like Cosmic Christ, take a year to complete — with the frame, which I sculpted, and then I had a woodcarver carve it.” His style is steeped in repetition, awash in tessellation, mosaic in effect, “like webs of infinite consciousness and interconnection.” How does he keep from going stir-crazy while painting all the details? Grey: “I just love the details. I love every aspect of painting. Everything about it.” What’s on yer mind while creating these two-dimensional thought sculptures? “Well, last night when I was painting I was doing mushrooms, and that kept me plugged into the universal aspect of creativity — ” Have ya painted under the influence of all drugs? “I’m most interested in the entheogens. “What’s helpful is, you come to a problem in a painting, and you want to get a different perspective on it, and so by smoking pot or otherwise looking at it from an altered state, solutions suggest themselves that may not have been obvious previously.” And what is art without music? “I listen to everything when I paint. Last night I was listening to Bach’s organ works played by Albert Schweitzer [post-War missionary doctor/author]. If you’re tripping, here’s a healer playing some of the deepest, most incredible music ever, some of the holiest, most sacred music…I also listen to Tool, Ramones, hip hop, trance music, techno, Gershwin, Philip Glass — everything, anything. I am attracted to the romantics, like Schubert, Beethoven, Bach — the heavy Germanic classical composers, as well as transcendental rock ’n roll like Jimi Hendrix and acid rock, Zeppelin, as well as Moby.” How’s the bread in this biz? “The Cosmic Christ piece got the most I was ever paid for a piece, and that was a hundred grand. It took a year. “Many of my works are not for sale, retained instead for placement in the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors. Those pieces could have been sold a dozen times — we could have made more money, but…” Ah yes, the Chapel. Alex and Allyson want to construct an elaborate twisted-pyramidal temple — a chapel — to shelter his famous series of paintings/constructions Sacred Mirrors. Enough has been written about those fabulous pieces, in snooty organs like Newsweek and The New York Times, so that everyone should know about them: twenty-one painted, mirrored figurative fantasies, each representing a mode of the body’s energetic capabilities, each festooned with carved atoms, chromosomes, planets, and stars. The paintings, which many cite as instruments of spiritual healing, long ago outgrew their cramped urban environment. Now they need a home where they can help people (the couple is currently investigating land near Woodstock). Having established a charitable organization, the Greys solicit contributions from individuals and organizations. Plug: Interested parties should visit the sacredmirrors.org website. As for the artist’s take on art, he says it’s simple: “I’m an indiscriminate art lover. I love it all. I like the transgressionist nihilist stuff; I like the sacred holy icons. Artists alive today, as cultures collide, have an opportunity to see it all and synthesize it into their own core vision and their own idiosyncratic understanding of the archetypes that evolved throughout art’s history.” He transforms tradition into something new, something not yet defined, sacred to space-age stoners as well as backwater aboriginals — something timeless, something yet to come. Grey: “The future of art includes every technological breakthrough and admixture of world culture that can be discovered. The challenge to an artist today is integrating the vast visual legacy of human culture with their own insights, distilling that into works of art, in whatever media, and making a living at it. “My special and personal interest is in exploiting the unique opportunity that Twenty-first Century artists have to create a more universal spiritual art. Our art will always have a function to interpret the world, to reveal the condition of the soul, however ugly, confusing, or transcendent, and to encourage and awaken the higher faculties within every individual. That's my mission, and I'm sticking to it.” Drop some acid and tune into Alex’s amazingly wonderful website: www.alexgrey.com. Also, check out the new Tool video, with graphics by Grey and guitarist Adam Jones. |

||||||||||||||||

Ever wonder what a person’s transpersonal energy vortex looks like? Or how about their interdimensional embryonic aura? Examine the sacred paintings of ALEX GREY and you’ll see such phenomena — and much more — lavishly depicted in living, loving color.

Ever wonder what a person’s transpersonal energy vortex looks like? Or how about their interdimensional embryonic aura? Examine the sacred paintings of ALEX GREY and you’ll see such phenomena — and much more — lavishly depicted in living, loving color.